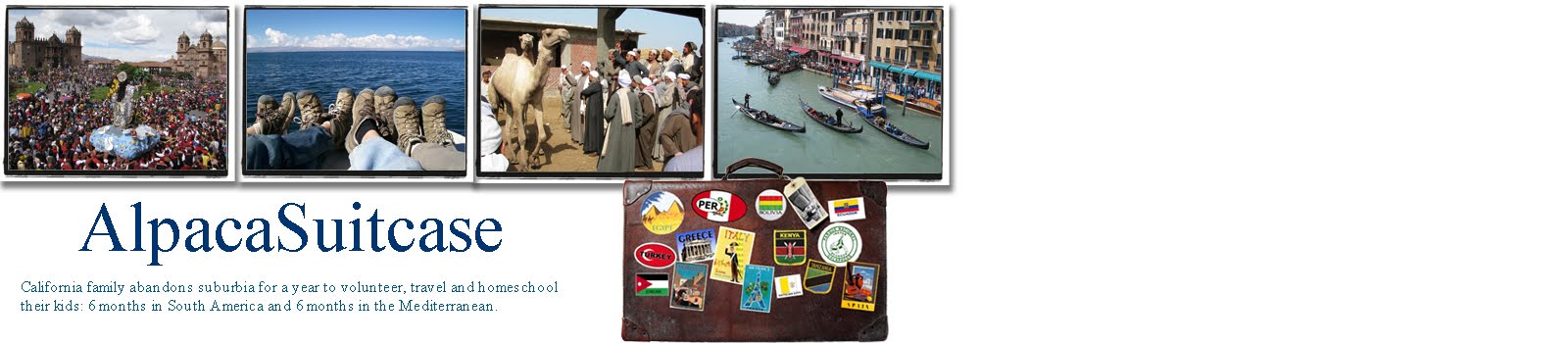

As a companion piece to the last blog entry on our Top 10 Literary Travel Books of 2010, I present our family’s Best Travel Movies of 2010. These are not the best movies we’ve seen, nor are they the best travel movies out there; they are the ten movies that most enhanced our family’s travel experience. (Present-day country in parentheses)

#1: HBO’s Rome (2005 - 24 episodes) (Italy): This two-season HBO series is not a movie but we saw nothing in the last year that educated us more…nor was more entertaining. From Julius Caesar’s rise to the fall of Antony and Cleopatra, we were captivated by every hour of this series that covered the fall of the Republic and the rise of the Empire. The characters were well-drawn and the acting excellent, with the added benefit that our kids now know their Cato from their Cicero. (For more on why our 14 and 12 year old kids were even watching this, go here)

#1: HBO’s Rome (2005 - 24 episodes) (Italy): This two-season HBO series is not a movie but we saw nothing in the last year that educated us more…nor was more entertaining. From Julius Caesar’s rise to the fall of Antony and Cleopatra, we were captivated by every hour of this series that covered the fall of the Republic and the rise of the Empire. The characters were well-drawn and the acting excellent, with the added benefit that our kids now know their Cato from their Cicero. (For more on why our 14 and 12 year old kids were even watching this, go here)#2: The Devil’s Miner (2005) (Bolivia): This little-known documentary is the story of 14-year old Basilio who works in the Potosi silver mine to support his family when his father dies. Taking a tour of the Potosi mine is harrowing and claustrophobic but this movie will put a human face on the experience. The movie is hard to find but available from sidewalk pirate-DVD sellers all over Bolivia. The title comes from the manner in which all the miners make offerings to the “devil of the mine,” the shrine that serves as an everpresent reminder that death can happen any at minute.

#3: The Motorcycle Diaries (2004) (South America): Gael Garcia Bernal stars as Che Guevara in his 1952 motorcycle tour of South America with his buddy Alberto. The Andean scenery and Gustavo Santaolalla’s music is a perfect backdrop for Che’s political awakening; the scene where he shares a campfire with Chilean miners and learns of their exploitation is particularly well done.

#4: The Dancer Upstairs (2002) (Peru): Another little-known movie which is directed by John Malkovich and is based loosely on the hunt and capture of Shining Path leader Abimael Guzman.(the movie makes no mention of Peru, Guzman or the Sendero Luminoso) Javier Bardem does a nice job as the lead detective and the movie gives you a sense of the tenseness and terror in Lima in the 1980’s during the time of the Sendero Luminoso.

#5: The Merchant of Venice (2004) Italy): Al Pacino does a creditable job as Shylock in this Shakespeare classic directed by Michael Radford. The story gives you an idea of what being a Jew was like in 16th century Venice, even though Shakespeare never set foot on Italian soil.

#6: Creation (2009) (South America, Galapagos): A recent movie about Charles Darwin’s relationship with his eldest daughter and how her death affected him. The movie portrays his internal conflict between religion and his scientific findings and it implies that his daughter’s death helped push him towards science. Many of his scientific ideas came from his 1835 visit to the Galapagos.

#7: Out of Africa (1985) (Kenya): Less about east Africa than about the colonial experience in Kenya, Redford and Streep play out their star roles amidst the beautiful Kenyan landscape. Based on the very good Isak Dinneson book of the same name.

#8: Roman Holiday (1953) Italy): A fun and light romp through the Eternal City with Gregory Peck as a reporter and Audrey Hepburn as a visiting Princess. Beautiful black and white cinematography.

#9: Alexander (2004) (Greece and Turkey): Not the greatest of movies and I’m not a Colin Farrell fan but it gives a good overview of Alexander’s short life. Alexander’s relationship with his generals (Ptolemy, Antigonus, Antipater, Seleucis, et al. ) who would carve up his empire after his death was of special interest.

#10: Troy (2004) (Turkey, Greece): Again not a great movie but an entertaining way to learn about Homer’s account of the united Greek city-states’ assault on Troy.